Wellcome Images, CC BY-SA

Chris Gosden, University of Oxford

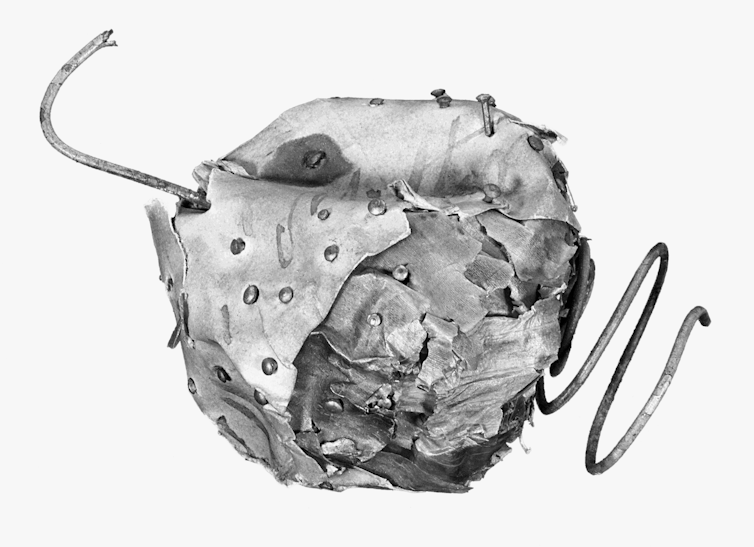

On April 16, 1872, a group of men sat drinking in the Barley Mow pub near Wellington in Somerset in the UK’s south-west. A gust of wind in the chimney dislodged four onions with paper attached to them with pins. On each piece of paper, a name was written. This turned out to be an instance of 19th-century magic. The onions were placed there by a “wizard”, who hoped that as the vegetables shriveled in the smoke, the people whose names were attached to them would also diminish and suffer harm.

One onion has ended up in the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. The person named on it is Joseph Hoyland Fox, a local temperance campaigner who had been trying to close the Barley Mow in 1871 to combat the evils of alcohol. The landlord, Samuel Porter, had a local reputation as a “wizard” and none doubted he was engaged in a magical campaign against those trying to damage his business.

E.B. Tylor, who wrote Primitive Culture, a foundational work of 19th-century anthropology, lived in Wellington. The onion came to him and thence to the Pitt Rivers Museum of which he was curator from 1883. Tylor was shocked by the onions, which he himself saw as magical. Tylor’s intellectual history regarded human development as moving from magic to religion to science, each more rational and institutionally based than its predecessor. To find evidence of magic on his doorstep in the supposedly rational, scientific Britain of the late 19th century ran totally counter to such an idea.

Pitt Rivers Museum, PRM 1917.53.776, Author provided

Rumours of the death of magic have frequently been exaggerated. For tens of thousands of years – in all parts of the inhabited world – magic has been practised and has coexisted with religion and science, sometimes happily, at other times uneasily. Magic, religion, and science form a triple helix running through human culture. While the histories of science and religion have been consistently explored, that of magic has not. Any element of human life so pervasive and long-lasting must have an important role to play, requiring more thought and research than it has often received.

What is magic?

A crucial question is, “What is magic?” My definition emphasises human participation in the universe. To be human is to be connected, and the universe is also open to influence from human actions and will. Science encourages us to stand back from the universe, understanding it in a detached, objective, and abstract manner, while religion sees human connections to the cosmos through a single god or many gods who direct the universe.

Magic, religion, and science have their own strengths and weaknesses. It is not a question of choosing between them – science allows us to understand the world in order to influence and change it. Religion, meanwhile, derives from a sense of transcendence and wonder.

Magic sees us as immersed in forces and flows of energy influencing our psychological states and well-being, just as we can influence these flows and forces.

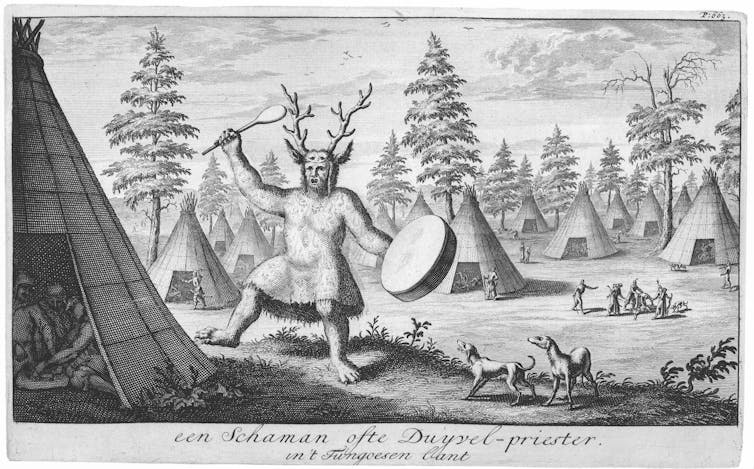

Magic is embedded in local cultures and modes of being – there is no one magic, but a vast variety, as can be seen in the briefest survey (for more detail see my recent book). Tales of shamanism on the Eurasian steppe, for example, involve people transforming into animals or travelling to the spirit world to counteract disease, death, and dispossession.

British Library. Nicolaes Witsen 1705, Amsterdam, Author provided

In many places, ancestors influence the living – including in many African and Chinese cultures. A Bronze Age tomb in China reveals complex forms of divination with the dead answering the living. Fu Hao, buried in the tomb shown below, asked her ancestors about success in war and the outcomes of pregnancies, but then was questioned by her descendants about their future after death.

Jessica Rawson, Author provided

Influential mages

British royalty employed magicians: Queen Elizabeth I asked Dr. John Dee, a well-known “conjuror” – and probable model for Prospero in Shakespeare’s Tempest – to find the most propitious date for her coronation and supported his attempts at alchemy.

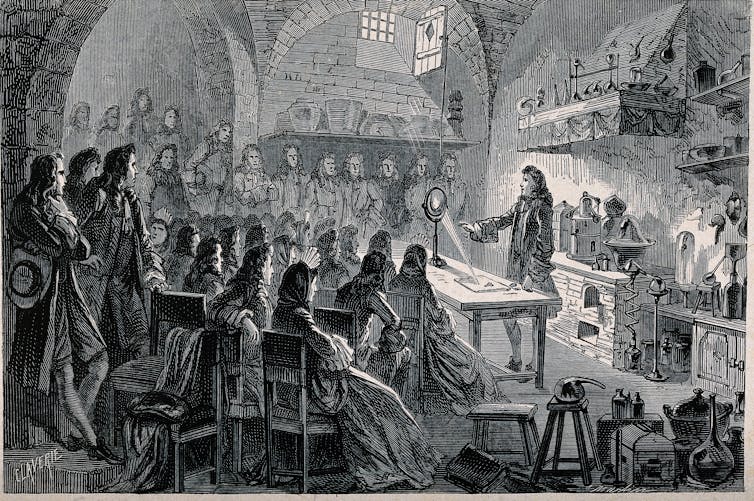

In the following century, Isaac Newton spent considerable effort on alchemy and Biblical prophecy. He was described by the economist John Maynard Keynes as not the first of the Age of Reason, but the last of the magicians. In the mind of Newton – and in his work – magic, science and religion were entangled, each being a tool for examining the deepest secrets of the universe.

Wellcome Collection, Author provided

Many across the world still believe in magic, which does not make it “true” in some scientific sense but indicates its continuing power. We are entering an age of change and crisis, brought about by the depredations of the ecology of the planet, human inequality, and suffering. We need all the intellectual and cultural tools at our disposal.

Magic encourages a sense of kinship with the universe. With kinship comes care and responsibility, raising the possibility that understanding magic, one of the oldest of human practices, can give us new and urgent insights today.![]()

Chris Gosden, Professor of European Archaeology, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.