Zapp2Photo/Shutterstock.com

Jeremy Straub, North Dakota State University

You’ve probably been told it’s dangerous to open unexpected attachment files in your email – just like you shouldn’t open suspicious packages in your mailbox. But have you been warned against scanning unknown QR codes or just taking a picture with your phone? New research suggests that cyberattackers could exploit cameras and sensors in phones and other devices.

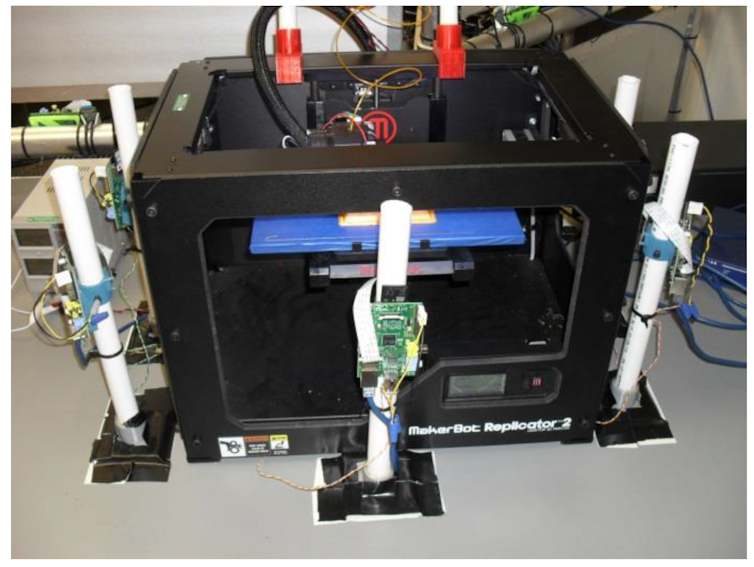

As someone who researches 3-D modeling, including assessing 3-D printed objects to be sure they meet quality standards, I’m aware of being vulnerable to methods of storing malicious computer code in the physical world. Our group’s work is in the laboratory, and has not yet encountered malware hidden in 3-D printing instructions or encoded in the structure of an item being scanned. But we’re preparing for that possibility.

At the moment, it’s not very likely for us: An attacker would need very specialized knowledge about our system’s functions to succeed in attacking it. But the day is coming when intrusions can happen through normal communications with or sensing performed by a computer or smartphone. Product designers and users alike need to be aware of the risks.

Transmitting infection

In order for a device to become infected or compromised, the nefarious party has to figure out some way to get the computer to store or process the malware. The human at the keyboard has been a common target. An attacker might send an email telling the user that he or she has won the lottery or is going to be in trouble for not responding to a work supervisor. In other cases, a virus is designed to be unwittingly triggered by routine software activities.

Researchers at the University of Washington tested another possibility recently, embedding a computer virus in DNA. The good news is that most computers can’t catch an electronic virus from bad software – called malware – embedded in a biological one. The DNA infection was a test of the concept of attacking a computer equipped to read digital data stored in DNA.

Similarly, when our team scans a 3-D printed object, we are both storing and processing the data from the imagery that we collect. If an attacker analyzed how we do this, they could – perhaps – identify a step in our process that would be vulnerable to a compromised or corrupted piece of data. Then, they would have to design an object for us to scan that would cause us to receive these data.

Jeremy Straub, CC BY-ND

Closer to home, when you scan a QR code, your computer or phone processes the data in the code and takes some action – perhaps sending an email or going to a specified URL. An attacker could find a bug in a code-reader app that allows certain precisely formatted text to be executed instead of just scanned and processed. Or there could be something designed to harm your phone waiting at the target website.

Imprecision as protection

The good news is that most sensors have less precision than DNA sequencers. For instance, two mobile phone cameras pointed at the same subject will collect somewhat different information, based on lighting, camera position and how closely it’s zoomed in. Even small variations could render encoded malware inoperable, because the sensed data would not always be accurate enough to translate into working software. So it’s unlikely that a person’s phone would be hacked just by taking a photo of something.

But some systems, like QR code readers, include methods for correcting anomalies in sensed data. And when the sensing environment is highly controlled, like with our recent work to assess 3-D printing, it is easier for an attacker to affect the sensor readings more predictably.

What is perhaps most problematic is the ability for sensing to provide a gateway into systems that are otherwise secure and difficult to attack. For example, to prevent the infection of our 3-D printing quality sensing system by a conventional attack, we proposed placing it on another computer, one disconnected from the internet and other sources of potential cyberattacks. But the system still must scan the 3-D printed object. A maliciously designed object could be a way to attack this otherwise disconnected system.

Screening for prevention

Many software developers don’t yet think about the potential for hackers to manipulate sensed data. But in 2011, Iranian government hackers were able to capture a U.S. spy drone in just this way. Programmers and computer administrators must ensure that sensed data are screened before processing, and handled securely, to prevent unexpected hijacking.

In addition to developing secure software, another type of system can help: An intrusion detection system can look for common attacks, unusual behavior or even when things that are expected to happen don’t. They’re not perfect, of course, at times failing to detect attacks and at others misidentifing legitimate activities as attacks.

![]() Computer devices that both sense and modify the environment are becoming more common – in manufacturing robots, drones and self-driving cars, among many other examples. As that happens, the potential for attacks to include both physical and electronic elements grows significantly. Attackers may find it very attractive to embed malicious software in the physical world, just waiting for unsuspecting people to scan it with a smartphone or a more specialized device. Hidden in plain sight, the malicious software becomes a sort of “sleeper agent” that can avoid detection until it reaches its target – perhaps deep inside a secure government building, bank or hospital.

Computer devices that both sense and modify the environment are becoming more common – in manufacturing robots, drones and self-driving cars, among many other examples. As that happens, the potential for attacks to include both physical and electronic elements grows significantly. Attackers may find it very attractive to embed malicious software in the physical world, just waiting for unsuspecting people to scan it with a smartphone or a more specialized device. Hidden in plain sight, the malicious software becomes a sort of “sleeper agent” that can avoid detection until it reaches its target – perhaps deep inside a secure government building, bank or hospital.

Jeremy Straub, Assistant Professor of Computer Science, North Dakota State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.