Rachel Plotnick, Indiana University

All day every day, throughout the United States, people push buttons – on coffee makers, TV remote controls and even social media posts they “like.” For more than seven years, I’ve been trying to understand why, looking into where buttons came from, why people love them – and why people loathe them.

As I researched my recent book, “Power Button: A History of Pleasure, Panic, and the Politics of Pushing,” about the origins of American push-button society, five main themes stood out, influencing how I understand buttons and button-pushing culture.

1. Buttons aren’t actually easy to use

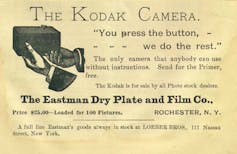

George Eastman Museum/Wikimedia Commons

In the late 19th century, the Eastman Kodak Company began selling button-pushing as a way to make taking photographs easy. The company’s slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest,” suggested it wouldn’t be hard to use newfangled technological devices. This advertising campaign paved the way for the public to engage in amateur photography – a hobby best known today for selfies. Yet in many contexts, both past and present, buttons are anything but easy. Have you ever stood in an elevator pushing the close-door button over and over, hoping and wondering if the door will ever shut? The same quandary presents itself at every crosswalk button. Programming a so-called “universal remote” is often an exercise in extreme frustration. Now think about the intensely complex dashboards used by pilots or DJs.

For more than a century, people have been complaining that buttons aren’t easy: Like any technology, most buttons require training to understand how and when to use them.

U.S. Air Force/Kelly White

2. Buttons encourage consumerism

The earliest push buttons appeared on vending machines, as light switches and as bells for wealthy homeowners to summon servants. At the turn of the 20th century, manufacturers and distributors of push-button products often tried to convince customers that their every whim and desire could be gratified at a push – without any of the mess, injury or effort of previous technologies like pulls, cranks or levers. As a form of consumption, button pushing remains pervasive: People push for candy bars and tap for streaming movies or Uber rides.

Alexander Klink/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Amazon’s “Dash” button takes push-button pleasure to the extreme. It’s tempting to think about affixing single-purpose buttons around your house, ready to instantly reorder toilet paper or laundry detergent. But this convenience comes at a price: Germany recently outlawed Dash buttons, because they don’t let customers know how much they’ll pay when they place an order.

3. Button-pushers are often seen as abusive

Throughout my research, I discovered that people worry that buttons will fall into the wrong hands or be used in socially undesirable ways. My children will push just about any button within their reach – and sometimes those not within reach, too. The children of the late 19th and early 20th centuries were the same. People often complained about children honking automobile horns, ringing doorbells and otherwise taking advantage of buttons that looked fun to press.

Adults, too, often received criticism for how they pushed. In the past, managers triggered ire for using push-button bells to keeping their employees at their beck and call, like servants. More recently there are stories in the news about disgraced figures like Matt Lauer using buttons to control the comings and goings of his staff, taking advantage of a powerful position.

4. Some of the most-feared buttons aren’t real

Beginning in the late 1800s, one of the most common fears registered about buttons involved warfare and advanced weapons: Perhaps one push of a button could blow up the world. This anxiety has persisted from the Cold War to the present, playing prominently in movies like “Dr. Strangelove” and in news headlines. Although no such magic button exists, it’s a potent icon for how society often thinks about push-button effects as swift and irrevocable. This concept is also useful in geopolitics. As recently as 2018, President Donald Trump bragged to North Korean leader Kim Jong Un over Twitter that “I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!”

5. Not a lot has changed in more than a century

As I completed my book, I was struck by how much voices of the past echoed those of the present when discussing buttons. Since the 1880s, American society has deliberated about whether button pushing is a desirable or dangerous form of interaction with the world. Persistent concerns remain about whether buttons make life too easy, pleasurable or rote. Or, on the flip side, observers worry that buttons increase complexity, forcing users to fiddle unnecessary with “unnatural” interfaces.

Staples

Yet as much as people have complained about buttons over the years, they remain stubbornly present – an entrenched part of the design and interactivity of smartphones, computers, garage door openers, car dashboards and videogame controllers. As I suggest in “Power Button,” one way to remedy this endless discussion about whether buttons are good or bad is to instead begin paying attention to power dynamics – and the ethics – of push buttons in everyday life. If people begin to examine who gets to push the button, and who doesn’t, in what contexts, under which conditions, and to whose benefit, they might begin to understand buttons’ complexity and importance.

Power Button: A History of Pleasure, Panic and the Politics of Pushing![]()

Rachel Plotnick, Assistant Professor of Cinema and Media Studies, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ugh! Now every time I see a button I’m going to overthink it. But this reminded me of watching the Jetsons ( kids’ cartoon laced with grown up logic) and the oft mentioned dilemma of too many buttons. It also reminded me if the year I was assigned the CEO in Secret Santa. ? (How every year I got one of the executives, I’ll never know. It was rigged.?) Anyway, one of the ‘gifts’ I gave the CEO from Secret Santa was an Easy Button. I figured he already knew how to use it. I might as well give him one.